Rural America still isn't buying electric cars: Here's how advocates are trying to change that

Zero-emission car sales have largely gone to wealthier, urban areas. Experts say it's due to two issues: infrastructure and cost.

Luis Olmedo is the executive director of Comite Civco del Valle, a health and environmental justice nonprofit in Imperial County.

"This is the world we have, and there's only a plan A," Olmedo said.

Olmedo, a second-generation environmental-justice advocate, said he believes electric vehicles are one of the ways we can help "turn climate change around."

"This is a planet that we need to conserve, we need to protect. And these are the technologies that are coming our way to make sure that they can they help us achieve that," he said.

But Imperial County has, until recently, received very little investment in the zero-emission transportation industry.

"And that's why Imperial today is in the very last, having the least per capita...of [electric vehicle] chargers in all California. And that's egregious," he said.

Statewide, more and more Californians are buying electric cars, but adoption is clustered in more urban areas.

State data shows zero-emission car sales have soared in the last 10 years - tripling from 2017 to 2021.

Nearly two-thirds of zero-emission cars bought in 2021 went to Los Angeles, Orange, Santa Clara, San Diego or Alameda County.

Click here to open this map in a new window

"This is stuff that has been available in abundance to large metropolitan areas, it just hasn't been available to rural America, to rural California, in the way that has been available other places," Olmedo said.

California Dreaming: The Road to Zero - How attainable are CA's zero-emission transportation goals?

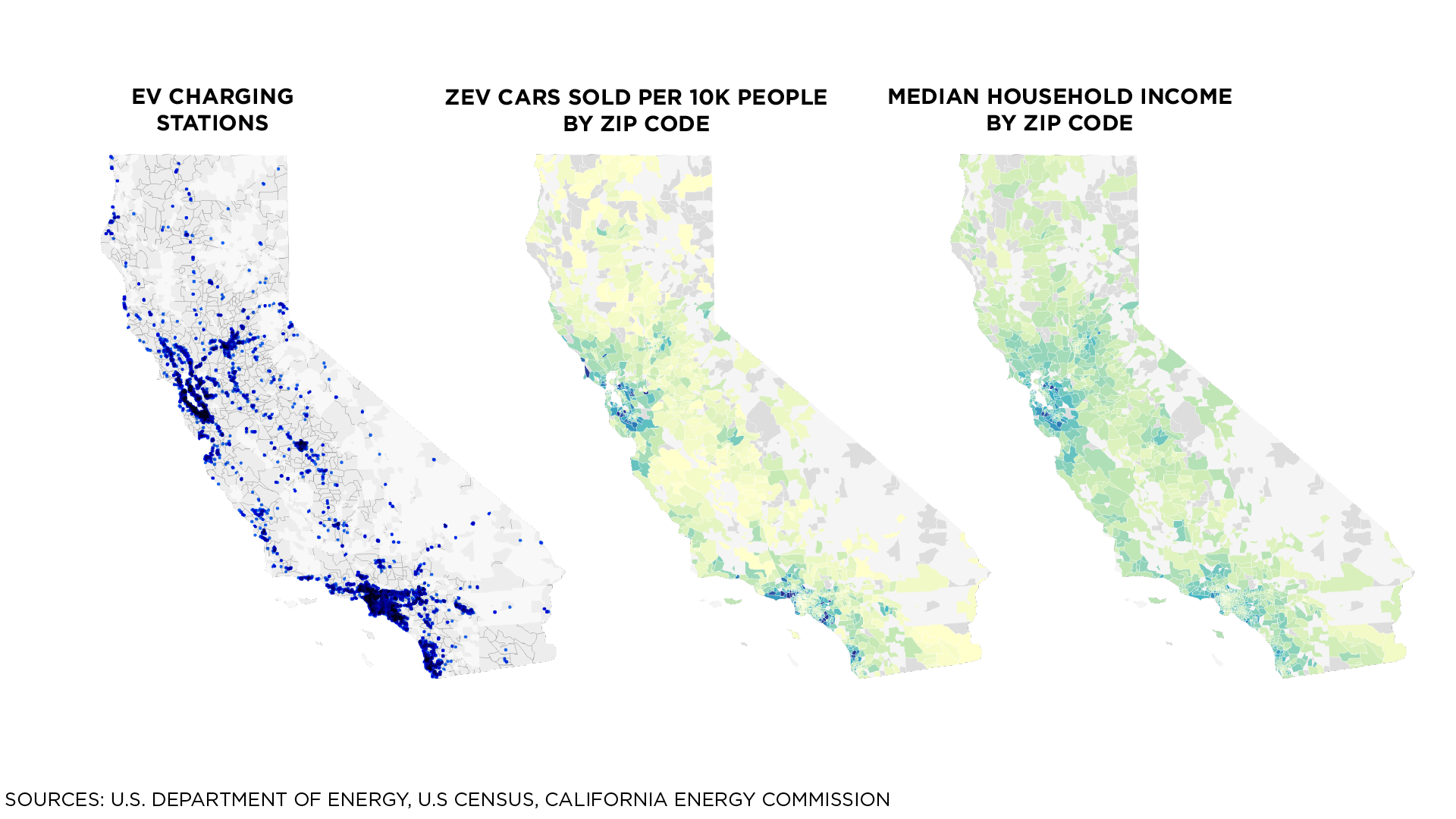

Maps of where charging stations are located, where people make the most money and where zero-emission cars are being sold all look very similar.

The similarity of these maps show that the spread of infrastructure has, in the past, happened in the same areas where people could afford these more expensive cars.

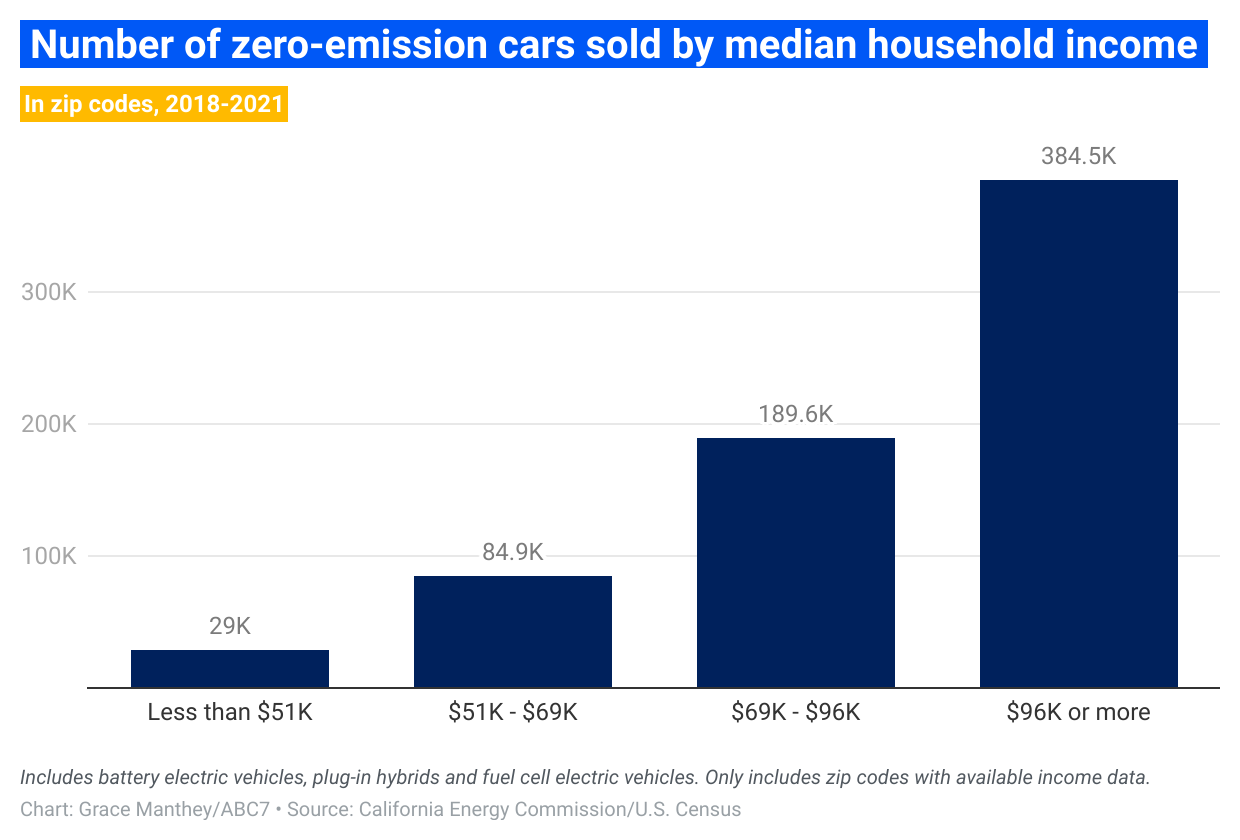

People in California ZIP codes in the lowest 25% bracket for median household income bought fewer than 30,000 zero-emission cars between 2018 and 2021. But people in the highest 25% bought more than 384,000 electric and plug-in hybrid cars.

"The same Californians who tend to live in communities most affected by air pollution, including pollution from trucks and cars, and other kind of on-road sources, they're the same ones that you would think we should be getting the access to the clean vehicles. But that's not always the case," said Colleen Callahan, a researcher from the UCLA Luskin Center for Innovation.

Ed Kim, president of automotive market research firm AutoPacific, said two things need to happen:

"The cost of the vehicles needs to come down, but the infrastructure needs to go up," he said.

Building out the infrastructure

Patty Monahan from the California Energy Commission said infrastructure for electric vehicles is the biggest challenge.

"We had over 100 years to build out refueling for gasoline vehicles. And now we want to do that in the next 10 years," she said.

Monahan also noted that the state will need 1.2 million public and shared electric vehicle chargers by 2030, and state data as of the end of April showed just under 80,000 chargers.

"So, we have a long way to go in terms of building out that infrastructure to meet the needs of the future fleet of zero emission vehicles that are coming," Monahan said.

President Biden's infrastructure plan includes nearly $400 million for California over five years to help build a network of charging stations.

But Monahan says the state is investing even more money.

"So last year, there was $900 million of general fund that came to the Energy Commission for the build-out of zero-emission vehicle infrastructure to refuel these vehicles. This year, the governor is proposing a $2 billion investment. And I should emphasize that it's for light duty, medium and heavy duty, hydrogen as well as battery electric infrastructure. So it's for all ZEV infrastructure," Monahan said.

One of the Energy Commission's programs is the California Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Project, which works with local partners to develop and provide incentives for EV charger installations.

More than half of the nearly $130 million invested have gone to disadvantaged or low-income communities, as of data through March 31.

Luis Olmedo and his nonprofit were able to facilitate the first charging station funded by the state.

But he said there's still room for improvement in historically underinvested rural areas.

"Even though the rebates are there, they're still far and unaffordable for a disadvantaged low-income community," he said.

Olmedo said once you apply to the program, you can get up to a $4,000 rebate per connector. But areas that don't have the right systems in place already need much more than that.

"The cost to build in a whole new electrical infrastructure is more in the proximity of $60,000 when it's all said and done. And that's because we've got to put in a new electrical system, new switch gear, new sub panels, new risers, this is all language I'm learning through this process," Olmedo said.

Charging infrastructure will be important to the 40% of Californians that live in apartments or condos and may not have the ability to charge their cars at home.

"Those people are going to have to depend on public charging infrastructure. And without that public charging infrastructure, all of those people really won't find an electric vehicle to be relevant to their lifestyle or their living situations. So you have to have the infrastructure in order to get less affluent people into those vehicles in the first place," said Ed Kim from AutoPacific.

Bringing down the cost

But Infrastructure isn't the only piece of the puzzle.

"This is kind of the classic chicken-and-egg question," said Tom Knox, executive director of Valley Clean Air Now, a nonprofit that helps residents in the San Joaquin Valley access cleaner transportation.

"We've found that our customers are very smart about how to make the most of the infrastructure that does exist in the valley," Knox said.

Grant Haver (who is not affiliated with Valley CAN) lives in the mountains of Squaw Valley in Fresno County and has a Tesla. He said if he's organized, charging his car is not a problem.

"The only downside...is if you're not organized with how you plan for your day, then you end up with a spot in the middle of the day where maybe you're running late to something and you're like, 'Well, no, I have to stop and charge for 27 minutes, the car says, to make it home,'" Haver said.

Haver said it would be nice if the charging stations were more on his way home.

"It's a five-minute detour, and it saves me filling up a tank of gas. So for me, it's absolutely worth it. It's a no-brainer," he said.

Knox from Valley CAN said it will be great when there is more infrastructure, but he doesn't "want to wait for that."

"And our customers have really shown us that it's better to get people into the cars. Let's, you know, make that behavior change. Let's show people this is possible," he said.

So how do they get people into these cars? They help with the cost.

"If we can be cost competitive with the older, gas-powered cars that we're really trying to get off the road, then it becomes a very easy choice for our customers to get into those cars."

Valley Clean Air now gets funding from the California Air Resources Board to help distribute incentives for people buying clean energy cars.

Many of these incentives are available statewide and many have provisions for low-income families.

"California has numerous incentives both financial and non-financial, to adopt advanced technologies," said John Swanton, an air pollution specialist at the California Air Resources Board.

"What we're trying to do is make sure that communities that need these vehicles the most are not left behind. And this is a transition that's actually happening with or without government intervention at this point. It may not happen as fast, but accelerating it is to the public's benefit," Swanton said.

"That's why we want to make sure that in this transition, it's a just transition. It's one in which communities are not left behind, and that communities that have been overburdened for decades with excessive emissions are not going to be subject to pollution going forward, simply because they can't afford the technology," Swanton continued.

But some programs seem to be reaching disadvantaged communities better than others.

Data from the state's Clean Vehicle Rebate Project shows that only about a third of rebate dollars given to individuals in 2021 went toward low-to-moderate-income rebates.

But numbers for the state's Clean Cars 4 All Retire and Replace program show almost 90% of participants were low income.

"Clean vehicles are used everywhere in California. So, you want to have a certain amount of rebate funds that are funding clean vehicles, regardless of where they're being used. But then you want to have a very targeted amount of money that can actually make vehicles affordable to California's residents that would be challenged to buy even a conventional new car," said Swanton.

Interested in an electric car? Here is a guide

Community organizations

But so many incentives can be confusing. That's where community organizations come in.

"That confusion also kind of ends up having the benefit of encouraging a lot of face-to-face interaction, and it ends up working really well once you've got a trusted community of voice that is there to explain what's possible," Tom Knox from Valley CAN said.

But there are more pieces to the puzzle: perception and awareness.

"I think in particular, that's where community-based organizations and other trusted messengers can come in. If you know that your neighbor just got an electric car, you're probably more likely to get one yourself, right?" Colleen Callahan from UCLA said.

So among all these factors, are the state's zero-emission transportation goals possible?

Luis Olmedo thinks so.

"I've seen a lot of projects being presented and opportunities being put in front of us. But this one feels very real," he said.

"It is going to happen," Olmedo continued. "I see no other future in front of us."